Under The Radar | Robert Campbell

by Charles Donovan

This article first appeared in issue 528 of Record Collector magazine (February 2022). Follow this link to read the article at the magazine website. You can also download a PDF copy of the article as it appeared in the print edition of the magazine.

By a strange paradoxical quirk of the 70s, artists who pretended to be gay or bisexual – Bowie, Bolan, Lou Reed – did extremely well out of its image-making capital, while the ones for whom it was the truth – Jobriath, Steven Grossman, Steve Swindells (all on major labels) – were consigned to undeserved obscurity. Only straight people, it seemed, could be publicly gay – a trend bucked solely by Tom Robinson.

In 1977, Decca quietly issued a kind of belated missing link between Transformer and Aladdin Sane, an album full of captivating, glam-adjacent soft-rock and balladry, with a gay sensibility that was no artificial PR gambit. It should have thrived, but Cardiff-born, Edinburgh-raised Robert Campbell’s Living In The Shadow Of A Downtown Movie Show lived up to its title by languishing in the half-light. Only when Martin Aston’s redoubtable history of LGBT pop, Breaking Down The Walls Of Heartache (2016), was published, did it get more attention.

“Nineteen-seventy-six was a very special year for many reasons,” recalls Campbell, who was toiling on two projects: a James Dean musical, Dean, and Tractorial Base, a futuristic concept work. He had also just met Carlos, his first love. “I was 20 and hadn’t had a long-term gay relationship before. While I was ‘out’ in my songs, it wasn’t something that everyone knew. I felt more comfortable singing about it – it was a way of saying ‘I’m gay’ without having to say it.”

An introduction to Decca was facilitated in March. “A friend of mine suggested I meet Jon Donaldson of the London Records division.” Campbell duly arrived at Decca studios on 16 March. “I was taken on a tour to Studio 1, which the Moody Blues had taken over as their Threshold Studios. Studio 2 was smaller and was the main studio for bands. And out the back was Studio 3, large enough for a complete orchestra.” Impressed by Campbell’s performances, Donaldson offered to manage him and proffered a £750 Decca contract.

One month later, Campbell was commissioned to compose music for the songs in an Edward Bond play produced by Gay Sweatshop, which brought him into contact with Tom Robinson, who’d been hired to play bass. “We hit it off immediately and spent a lot of time together. This was one of the hottest summers in London and the combination of the heat, being part of a gay show, being in love and that love becoming legal as I turned 21, made it a very liberating summer.”

Although Chrysalis put in an offer, Campbell took the Decca deal. Chris Demetriou signed on as producer and the album was to be orchestrated by Paul Buckmaster, until scheduling conflicts forced him to cancel. “In the end that job went to Brian Gascoigne, brother of Bamber.” Campbell demoed songs on a Phillips reel-to-reel, singing ideas for string and brass parts. Recording took place at Decca’s Studio 2, mainly live. “I realised I was totally out of my depth. Here I was with musicians I would never have normally worked with. But by the end of the day, the songs were sounding amazing and I knew it could work.”

Campbell’s cinematic, very urban songs, cloaked in dramatic movie-music arrangements played by the David Katz and Martyn Ford orchestras, sounded like a logical extension of what Bowie had begun on his more florid pieces (such as Time), with John Bundrick’s restless, tumbling piano standing in for Mike Garson’s.

By February the following year, everything was complete. Even though songs had been drawn from different projects, with I’ve Been Here Before and Villa Capri taken from the Dean musical, the eventual running order hung together remarkably well to form a series of mysterious, interlinked, subtly homoerotic story-songs about city life.

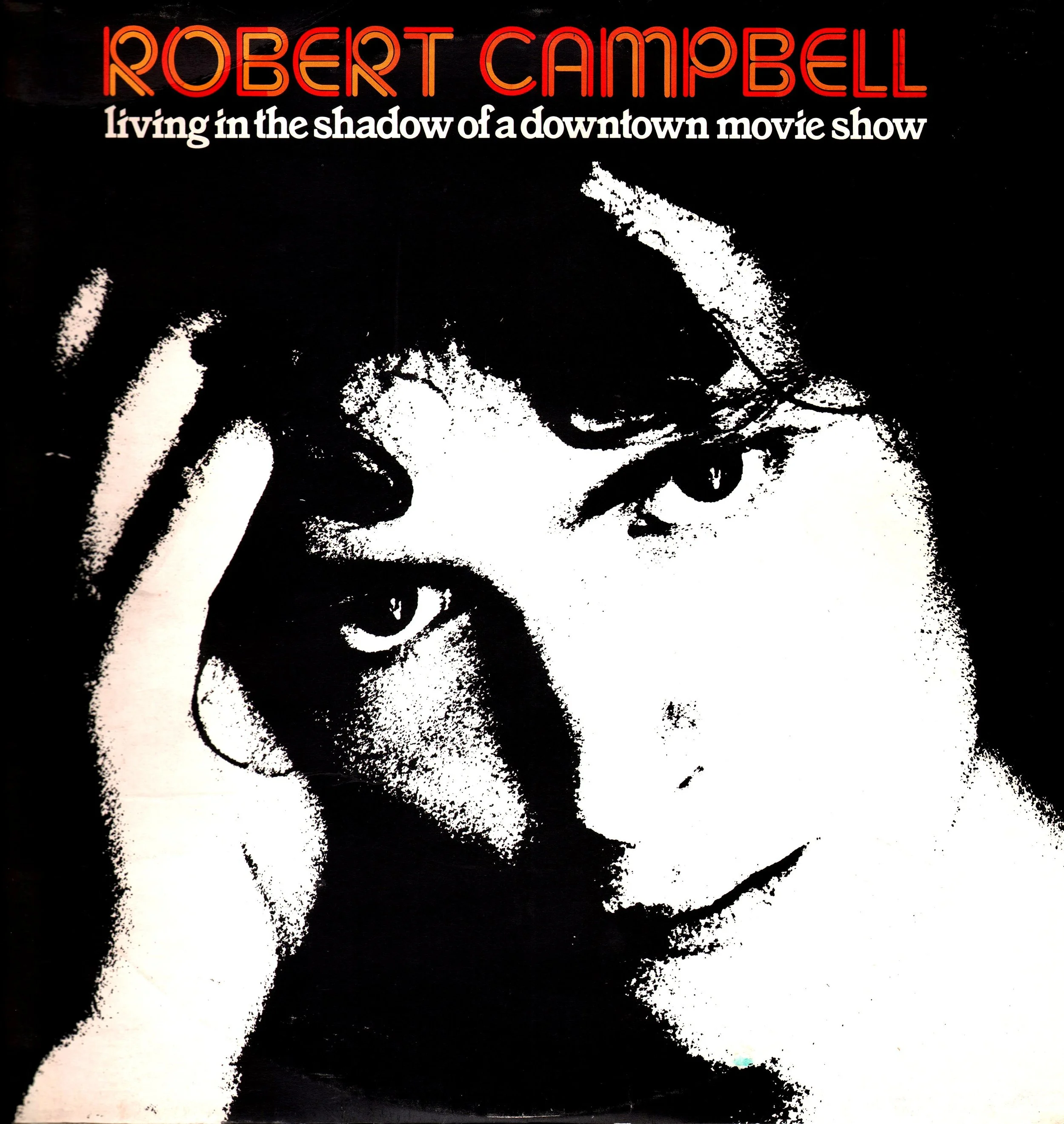

The cover bore Campbell’s face in xerox, his name rendered above in a rather awkward typeface. The reverse was more appealing: male-model cheekbones, an impassive stare and rockstar curls. One significant difference marking him out from Bowie and Reed was that where they made a feature out of being arch, brash and insincere, Campbell’s songs were earnest (in the best sense) and full of yearning, with a David Ackles-like masculine sensitivity quite at odds with glam. “I’ve always wished I’d been born a few years earlier to coincide with Neil Young and Joni Mitchell,” he tells RC. “I felt closer to the singer/songwriter tradition.”

Word came that Decca wanted to push opening track, Dreamboy, further down the running order, so as to conceal the album’s most obviously gay lyric, “making love to my dreamboy”, but Campbell stuck to his guns. “I remember wondering what my parents would make of the album. I played it to them in Scotland. But even though I was saying, ‘Listen – I’m gay,’ in songs, they wouldn’t talk about it until several years later. After my father died, I found that he’d collected reviews of the theatre shows I’d been involved in. I was touched but wondered why we couldn’t have been open while he was alive.”

Despite an abundance of winning melodies, the album hit the market without the benefit of a single. “Decca were unsure what to do with me, but then Dean started happening. They decided to launch the album to coincide with the West End opening and combine the promotion of the album with the show, which opened at the London Casino [now the Prince Edward] in August 1977. On the front of London buses, there was a poster for the show on one side and a poster for the album on the other. When the show wasn’t a success, Decca lost enthusiasm.” There would be no gigs undertaken in its support.

A follow-up was planned but soon Decca and Campbell parted ways, the latter moving on to Jet Records as part of a duo. “We recorded an album at Marquee Studios,” he recalls. “I was so obsessed with trying to write ‘the single’ that I lost direction. The lyrics reverted to ‘you’ and there was very little explicitly gay about the album.”

It remains unreleased. Since moving to Spain, Campbell has taught English, set up a publishing company, and become a full-time author. “I still pick up the guitar every day and occasionally get out and perform,” he says. “My obsession with James Dean continues and I’ve written more Dean-related songs. And, yes, I’m still with Carlos.”